The compound was discovered at Firmenichin the early 1960s as an analogue of methyl jasmonate, a key component of jasmine oil. Gautier has no doubt about the value of Hedione (methyl dihydrojasmonate), used in almost all fine fragrances and Firmenich’s top seller in terms of volume.

But which fragrance compounds are most valued by industry - a kind of fragrance top 10? It’s a difficult question to answer. To make a fine fragrance, new molecules are mixed with old favourites. Looking back at perfume trends, it is clear when chemical breakthroughs have taken place in the industry, says Gautier. When the perfumers take a liking to a new molecule, it’s often not long before new fragrances bearing the signature compound hit the high street. He gets the feedback from his colleagues on what consumers want and interprets the information in olfactory tonalities,’ explains Toni Gautier, corporate vice-president of R&D at Firmenich. ’We have one very special person who is a chemist and also an excellent perfumer. If you love a certain molecule it can be frustrating if you see that other people don’t like it,’ says Kraft. ’Sometimes it can be that a few love your molecule, while some hate it. Fragments of known fragrance molecules can also be incorporated.Īny new fragrance molecules created in the lab are assessed by perfumers. If you like something then you can follow up a certain aspect,’ says Kraft.

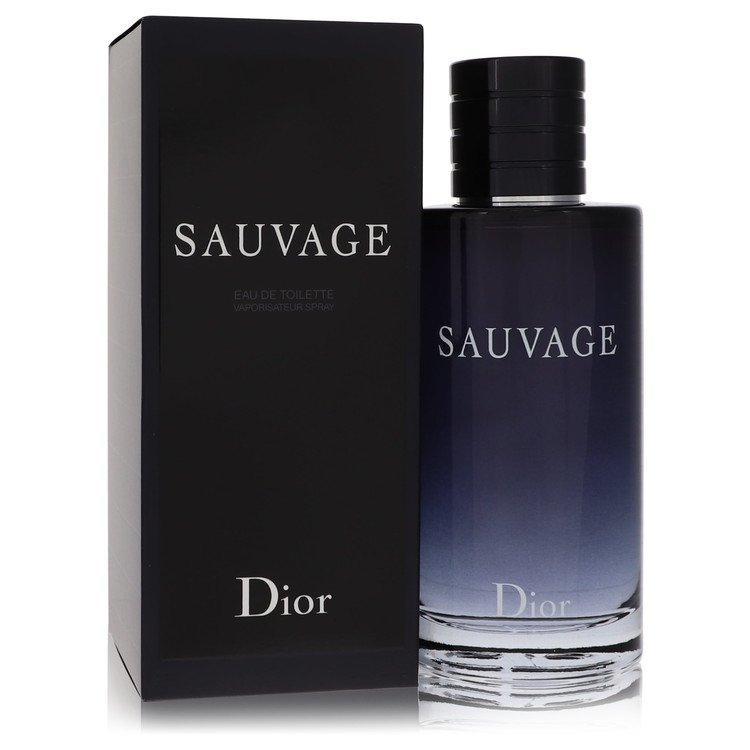

#Sauvage dior for men series#

’You can have chemical inspiration - you take known odour compounds and submit them to a specific series of reactions to see how the odour is modified. ’Or you can make the molecule more flexible to add new by-notes - you can cut some parts to make it lighter and more diffusive while conserving its overall shape.’īut his team sometimes takes the more traditional approach to creating captive ingredients. Adding rigidity to molecules often gives more defined odour notes, he adds. ’You can play with conformational elements that drive a certain molecular shape - for example you can introduce structural elements that cause a molecule to fold itself into a horseshoe shape and thus smell musky,’ explains Kraft. They also use olfactophore models, which show the molecular features that are key to a given odour, such as hydrophobic groups, and H-bond donors and acceptors. Kraft and his team frequently work on paper, sketching out molecular variations using ball and stick models. ’Often I make a molecule just to see how it smells.’ You look at the molecule, make a hypothesis as to why it smells like it does, and then test this hypothesis by modifying the molecule and seeing if you get the odour you desire,’ he explains. ’When I smell an odour I can almost see the shape of the molecule.

Kraft likes to follow a ’hardcore design approach,’ twisting, tweaking, and trimming existing molecules to modify odour and its intensity. ’What is now happening is that we are looking at trace compounds - a lot of these have low thresholds or are relatively unstable.’īut much of the work is done by altering existing molecules, or by searching for commercially viable synthetic routes for known compounds. The easily accessible fragrance ingredients were identified a long time ago, explains Koenraad Vanhessche, director of product and process research at Firmenich, another Swiss flavour and fragrance company. Givaudan, for example, runs its much-publicised ScentTrek missions to remote parts of the world to capture new smells. The chemistry is challenging: ’It’s tough work and despite all the molecular design tools, you still have to be lucky,’ he says.įragrance researchers search high and low for chemical inspiration. He creates patent-protected ’captive ingredients’ for Givaudan to hold in its fragrance arsenal. ’He had sent fragrance compounds to a company for evaluation so I wrote to that company and they sent me some materials, which I even used to give courses at school.’Īlmost three decades on, Kraft is still entranced by fragrance molecules. Kraft was captivated by an article by Peter Weyerstahl, a fragrance chemist who had modified the odour of rose oxide. The shop assistant was most amused and gave him a test subscription to a chemistry journal - Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. A year later, his questions still unanswered, Kraft returned to buy a chemistry textbook.

As a 12-year-old with a desire to understand the science of teenage hormones, he bought a biochemistry textbook from his local university bookshop in Hamburg, Germany. Kraft was drawn to fragrances and science at a very young age.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)